Women of Achievement

1992

DETERMINATION

for a woman who solved a glaring problem despite

widespread inertia, apathy or ignorance around her:

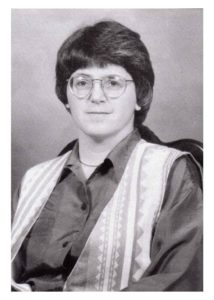

Dorothy “Happy” Jones

Dorothy Snowden “Happy” Jones was a Memphis homemaker with three daughters and a full slate of volunteer work centered around the Republican Party and the Junior League in the mid-1960s. She was a daughter of a wealthy, conservative family which considered civil rights an idea that should be stopped because black people did not deserve equal rights or equal respect.

From that upbringing Happy stepped into the confusion and turmoil of 1960s Memphis with personal conviction and strength. Since then she has been an active participant and leader in the civil rights and women’s rights movements.

As a coordinator of the Concerned Women of Memphis, Happy led a march to Mayor Henry Loeb’s office to protest poverty, racism and the city’s failure to negotiate in good faith with the city’s sanitation workers even after the death of Dr. King. As a charter member of the Memphis Panel of American Women, she began to speak to groups in the area about racism. She became a member of the Memphis and Shelby County Human Relations Commission, but when she learned it had no real power to change government she drafted legislation creating the Memphis Community Relations Commission and served as its first chairperson from 1972 to 1974. The Commission began addressing practical ways to change the systems that had led to the discrimination and institutional racism that kept most black Memphians poor and powerless. Along with the 22-member Commission board and executive director Rev. James Netters, Happy organized a Police-Community Relations Board to address police harassment of blacks.

Happy’s long-standing commitment to the Panel of American Women led her to serve as the project director for a grant awarded by the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare in 1975. She organized a conference demonstrating how optional schools could improve the quality of education in Memphis and be a desirable and functional alternative in the desegregation process. Because of her effort, there now are exceptional optional schools in the Memphis City Schools system.

The Commercial Appeal named Happy one of the 20 most influential political leaders in Memphis in 1968. Ever since then she has continued her work. She was a founder and first president of Network, served on the Urban League board, the Governor’s Jobs Conference, National Conference of Christians and Jews, and the YWCA nominating committee and advisory board. She developed her skills and became a professional family therapist.

Happy’s life is a story of pure determination to improve her city and the lives of her fellow citizens.

Happy died in 2018.